The Core Flaws of Modern AI based on Large Language Models (longpost)

There are so much noise about AI going on, and I would really like to clear out some confusion created by it. My original idea was to make a series of articles describing the mechanisms of Large Language Models (LLM) and particulary Transformer architecture to create a foundation of understanding of LLM-s for people without PhD in machine learning, because so many LLM-s are being packaged as black boxes while hiding their defficiencies, and barely anyone is taking their time to actually explain the areas where LLM fails, common mistakes it makes, why it’s absolutely not possible to fix them with the current tech, and why for some jobs you absolutely have to have an expert at least doing the final press of “accept solution” button.

However, I realized the amount of details I want to describe is just unacceptable, and most people don’t really care about it anyway. Good news is I can limit the description to mostly properties of the building parts of LLM/transformers rather than show how these parts work in details (the article is still huge though).

The key points of the article:

- Transformer is a good translator;

- Transformer has no model of world;

- As a result, transformer is absolutely terrible at solving truly novel tasks;

- Transformer is good at parroting i.e. reproducing similar known solutions;

- But even basic math has too many solutions to memorize, so Transformer is unreliable at math;

- Transformer is fundamentally unreliable, small fluctiations of input can lead to unpredictable results;

- Transformer is good at pretending to be an expert without being an expert;

- Chain of thoughts alleviate the problems, but eventually fail the same way.

The aspects of LLM-s most responsible for the success of LLM-s are actually the core machine learning algorithms, like backpropogation, continuously differentiable functions, and hardware capable of doing these operations on the extreme scale — many different transformers and non-transformer LLM-s exist and they all share similar problems, hence talking about single model (like LLaMa) is not very productive for the purpose of this article. And it’s not even about precise math, because reduction of LLM parameters to 8 and even 4 bits keeps like 90-95% of the performance of 16/32-bit LLM… Well, actually it’s about the math never being precise, but more on it latter.

Still first we need to examine the outline of Transformer architecture.

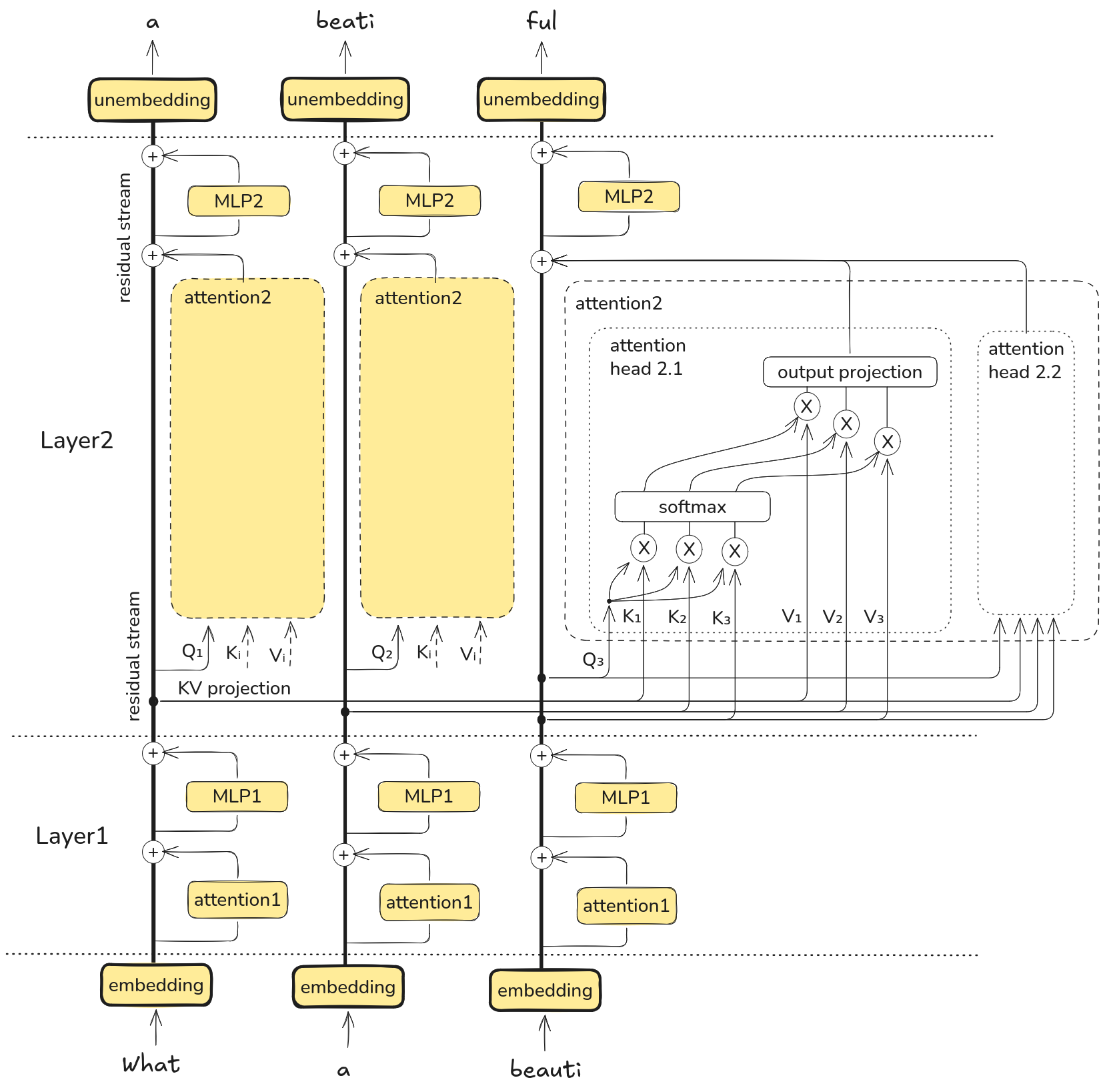

Transformer

(normalizations and position encodings are not shown, linear projections are considered simple connections, each “column” represents the same processing pipeline applied to a new input token)

MLP — https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Multilayer_perceptron a.k.a. Feed-Forward Network a.k.a. the most general and unpredictably inprecise way to approximate unknown relation between input and output, provided we can feed enough input-output pairs to train it. Dead simple core building block representing approx 2/3 of a common Transformer model parameters.

It was empirically found long time ago that universal predictors like Decision Trees, Support Vector Machines, and the MLP-s all follow same scaling law: logarithm of model’s parameter count is proportional to logarithm of its precision (usually formulated in inverse terms though).

Scaling law is basically: each additional parameter allows you to approximate one more additional point of output and requires a fixed additional amount of training data. Do note that I’m implying fixed input dimensions here, we only change internal parameters.

When the precise equation of scaling law for LLM-s was determined experimentally, it was mostly interpreted as “now we know how to scale our LLM-s in an optimal way”, not “our LLM-s are dumb black box predictors and scaling them gives diminishing returns” — the latter being much sober reality. This is not a strict proof, of course, but in a bigger picture with all other variables fixed (dataset curation, training methods, model architecture) and only model scale is being changed in unison with training dataset scale the larger model simply remembers more data points, more key-value pairs, finer input-output relations. Which is still a good result, but more on it latter.

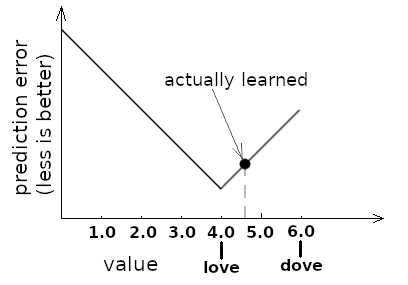

The core problem with MLP can be described by the following picture of output prediction error vs single output value graph:

It’s almost love, but it could be love

Both input and outputs of MLP are real numbers i.e. the values of varying precision. Here, the value 4.0 represents the word “love” and value 6.0 represents the word “dove”. The 5.0 represents god knows what and 4.7 point also represents “near love” value.

If you’ve ever been into any jobs requiring strict decisions, like math or coding, you know that not giving an answer is better than producing garbled answer. However, for the machine learning algorithm based on continuously differentiable functions being near the correct answer is actually the best achievable result. It’s possible to train MLP to exactly output 4.0 or 6.0, however, it is only possible on a priori known inputs, and if you trained MLP this way you would get sudden unpredictable shift of output on unfamiliar inputs — so-called “overfitting”. Actually, for this very reason it’s undesirable to exactly match 4.0 or 6.0 values — because MLP would react to the novel output so aggressively it may produce some crazy values e.g. offset by 6.5 when 4.5 experted.

This imprecision is an inherent problem of all the models (not only MLP) trained via gradient backpropogation, because backpropogation requires all intermediate functions to be continuously differentiable (or close to being so) i.e. no sharp steps, no precise switches.

However, despite all these problems there is one huge advantage of MLP with basic gradient backpropogation over DTP or STE-based backpropogation or GRU-based cells or others: being simple, universal, and capable of mass training and inference on existing GPU-s with off-the-shelf software like PyTorch or TensorFlow.

Still, a simple MLP cannot be employed alone because human language is sparse, repetitive, and context-dependant, while adding each new independant input into MLP increases training complexity exponentially (do not confuse independant inputs with internal parameter count). In simple words, doubling input count in MLP requires thousand times more training.

Notably, same goes for image and video processing — the information is sparse and repetitive, so transformers were applied to these areas too.

There’s a biger problem with simple MLP predictors-classifiers: they can learn simple well-defined inputs, but when you provide them with a mix of many different inputs it hasn’t been trained for, the result is unpredictable — independant decision forces pull it into different directions so the one that pulls a bit harder wins, but the result is usually not a correct prediction.

So we need to preprocess the input i.e. filter, pack, clean up before MLP can process it. How can we do it? Earlier things like GRU and LSTM-based models used to aggregate/refine the “meaning” of sparse context step-by-step into a single fixed-size vector: word2vec, GloVe, context2vec, ELMo — they also required lots of training and the capacity of fixed-size vector to store the context representation was limited.

Attention mechanism. Transformers were not the first ones to employ attention, however, transformers were the first to make it a workhorse i.e. dedicate lots of RAM and computational power to it. Original 2014 research suggested only Q and V vectors, one V for input token and one Q for each output token:

https://arxiv.org/abs/1409.0473 - Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate. Bahdanau, Cho, and Bengio (2014)

The 2017 transformers raised the stakes by creating self-attention with Q, K, V for each token, and these repeat for each layer — in the end it is incredibly space-inefficient (i.e. taking lots of VRAM), so lots of research is dedicated to reducing the footprint. Even small optimized models like Qwen2.5 14B take 2-4 Gb of VRAM just for a small 32k context window (approx. 24k words).

Arguably, “just store all the previous per-word/per-token data and let the model address it arbitrarily” was a straighforward solution that was almost feasable at that time, with a nice bonus — you can train the model in parallel, without waiting for previous steps to complete before doing the next step. At the cost of space inefficiency, of course, because you need to store all the intermediate data at the same time. Still more efficient than brute force scaling MLP.

Once again, important point: attention is not about being smart, it is about being one of simple aggregation mechanisms you can build with TensorFlow and Nvidia GPU, train for billions of iterations, and it scales.

It was not a simple coincidence that Nvidia released their first GPU with tensor cores same year (2017) — the GPU-s finally enabled brute forcing through this less inefficient model that would not be viable just several years before 2017. Do note that the 2017 models had 63 and 213 millions parameters — even for google 1 billion was too much at that time.

I had a conversation with a man who was working in ML at that time and he described a similar concern: “the model sounded interesting, but required absurdly large amount of training data and computing power, so we considered it not practical”.

Do also note that sometimes there is no excuse for this space-computation price paid for the attention — second half of transformer layers do not employ attention much:

https://arxiv.org/html/2505.13898v2 — Do Language Models Use Their Depth Efficiently?

Concrete example, pruning 27% of model and replacing the pruned layers with simple MLP-s leds to a minimal drop in performance:

https://arxiv.org/html/2403.03853v3 - ShortGPT: Layers in Large Language Models are More Redundant Than You Expect

And sometimes simplified single attention head is enough:

https://arxiv.org/abs/1905.10650 - Are Sixteen Heads Really Better than One?

This brings us to my big thesis: LLM-s are not cleverly designed mechanisms, but rather primitive templates with rough empirically picked shape that is just enough to solve basic NLP tasks, and it can only be trained via brute force of thousands GPU-s and terabytes of training datasets.

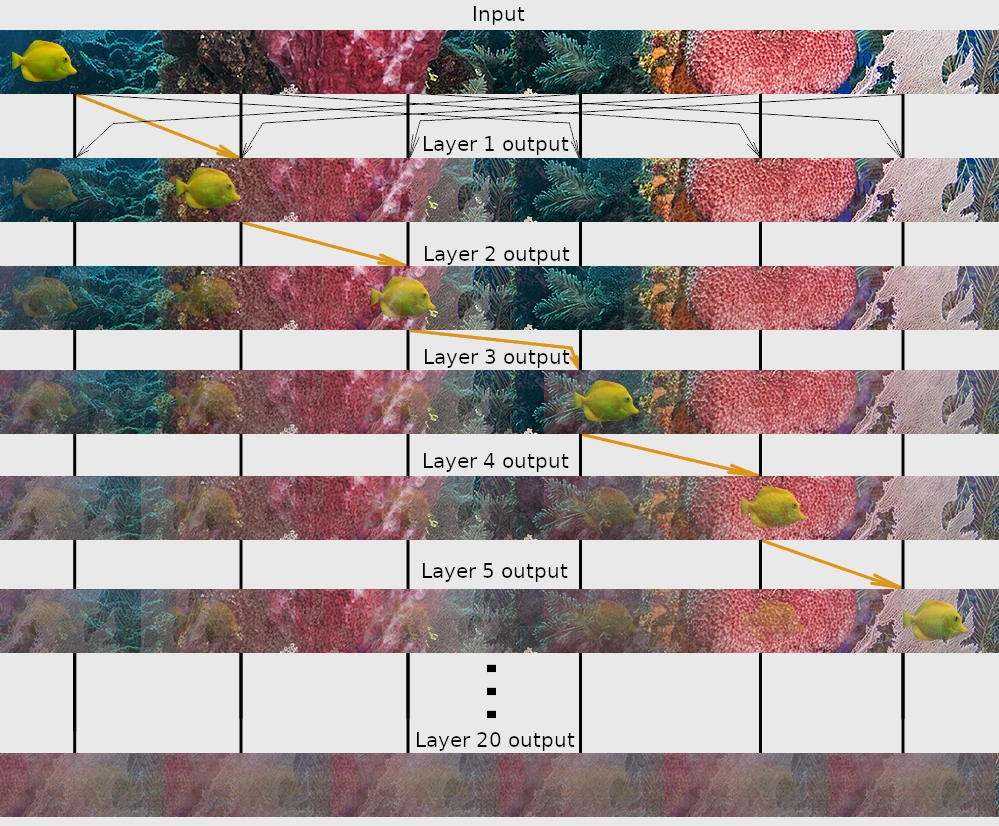

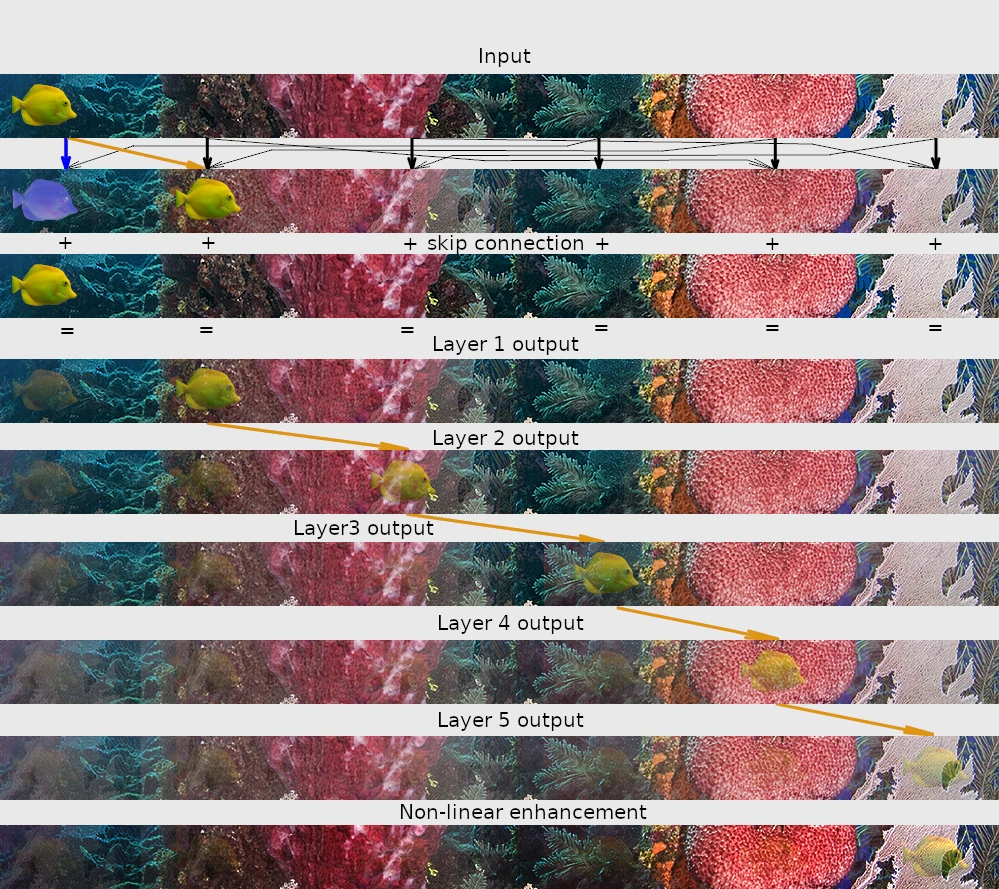

Let’s examine one of the core properties of the attention mechanism. In the transformer there are forces inherently dragging it toward rank collapse (information averaging). That is, attention is mixing several vectors from different residual streams in a non-precise way, meaning the whole information gets eventually smeared-averaged over multiple layers into same faceless sludge, same value for each token. The only two things saving it from the collapse are residual connections re-injecting current token and MLP doing non-linear re-sharping of the vector to restore the precision of smeared data. More math details in:

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2103.03404 - Attention is not all you need: pure attention loses rank doubly exponentially with depth

So I made a simple illustration of how would repetitive applications of attention to the data look like. Here some imaginary multi-layer processor is moving the yellow fish to a neighbouring right block, but in a non-presice way, so small amount of data gets mixed into less relevant parts of the image (top to bottom information flow):

I’ve run a simulation of 20 such layers and got the completely messed up output at the end — do notice that we kinda have information, but it’s being repeated over and over again. Basically it’s the average of 6 blocks repeated 6 times.

Now if we add “residuals” i.e. original inputs at each stage, the picture changes:

The final row is a non-linear tone transformation, depicting a result of some imaginary non-linear transformation i.e. MLP applied to the data — recovering some of the contrast this way.

Do note two important properties of the second (more transformer-like) example:

- The output remains more like the original input;

- The newly produced information (i.e. yellow fish) is suppressed.

And still MLP+residuals are not enough to guarantee convergence (i.e. to make the model learn a stable picture rather than run around the house while screeming naked) because classic 2017 transformer can actually enter non-linear mode via erasure of residual stream subspace i.e. x + (-x) = 0 on some narrow inputs. Once again, you cannot differentiate such a function, and the derrivative is required to backpropogate gradients of loss function.

For similar reasons gumbel-softmax, sparsemax, entmax-based attentions are sharper but rarely employed for anything beyond small research prototypes.

Do remember what I wrote about MLP being imprecise? Here, once again, precise operations are harmfull for the model training process, so being precise is unacceptable. MLP gives imprecise prediction of black box relation, attention mechanism gives imprecise aggregation of features from multiple inputs (tokens), and you need that precision to implement strict logical deductions.

Some degree of erasure from residual stream (x + (-x) = 0) is actually required for LLM to work correctly, at least to replace inputs with output, because same residual stream is used for both. So industry went for a workaround in the form of extracting post-normalization from the residual stream and placing it back as pre-normalization of nested processing blocks i.e. processing blocks never see actual scale of input values in the residual stream, making it extremely difficult for the model to place back exactly opposite value into the residual stream — which is both advantegeous (gradients keep flowing) and disadvantageous, because you have some guaranteed amount of noise always present in the stream and each stage forced to account for it.

LLaMA, Mistral, Gemma, Qwen, DeekSeek all employ this incomplete erasure — it’s like trying to reuse same piece of paper by blurring old text and writing new one with larger letters and darker ink.

Do note that per attention mechanism within same layer you are not allowed to read outputs of previous iterations of the current layer, so the only way to perform logical deduction within classic LLM-s is by one way chaining between layers e.g. Layer 2 employing results of Layer 1, Layer 3 calculating consequences based on Layer 2 results, etc.

However, the rank collapse i.e. information smearing in softmax-based attention makes each next stage of deduction less and less precise, not putting a hard limit onto processing depth but rather imposing a precision tax onto each subsequent deduction.

The problem can be partially alleviated by chain-of-thoughts mechanism actually looping the output of latter layers back into layer 1, however, chain of thoughts still does not fundamentally resolve the precision problem — it only makes the difference between failing eventually and failing miserably.

The birth defect of LLM-s

The task which every LLM I’ve tried have failed is “shuffle these words in random order: …” — 30 words are guaranteed to confuse even largest models, it can only correctly shuffle the words via external tools e.g. python script (like Gemini does). It’s just a good demo of how attention fails to keep track of strict relations between words due to MLP imprecision plus information smearing plus residual noise.

Another example: recently I tried to reproduce the stylometry results from https://aclanthology.org/2022.repl4nlp-1.26.pdf, and got even more awful results from it. The reason is the same: transformers prefer bird-eye view of the content and just cannot grasp precise details, it sticks to discussion topics instead of recognizing fine details of author’s style.

Latter attempts of other researchers to solve the problem with transfomers (https://arxiv.org/pdf/2410.12757) employed GPT-4 for generation of training data that would capture the required fine details while disregarding the topic. The final model trained on GPT-4-generated data still sucks (80% accuracy, compared to 90-95% for hybrid algorithms), but it’s rather notable that GPT-4 can actually grasp stylistic differences — due to the aforementioned scaling law i.e. if your model loses fine details then just enlarge it by x10-x100 until the precision is enough. However, employing GPT-4 for stylistic analysis is like fitting Nvidia H100 into a electric kettle to make it boil watter in response to voice commands — just as insane of an overkill as it is for the simple task of determining “how often this person places a space before a comma”. And that is the cost of imprecision, information smearing, and residual noise caused by training methods.

In the church of end-to-end training and loss gradient backpropogation it’s not possible to fix the precision problem, because precise answers mean sharp decision i.e. discrete non-differentiable functions through which gradients cannot be passed. So precise model cannot be trained with these methods, MLP will always remain “almost precise” to a varying degree, attention will be almost able to make logical deductions — you can work around the imprecisions but you cannot solve them.

This birth defect is shared by pretty much any model trained end-to-end via gradient backpropogation, be it GPT-family, LLaMa-family, Mamba, or some kind of diffusion tranformer, whether you are employing absolute sinusoidal position on embeddings or relative rotation for Q-K vectors — those are just different flavorings for the same stale meat. That’s why I feel like there is really no point in trying to explain “how ChatGPT works”, because it’s all a mess of directed randomly (“stochastically”) guessed parameters.

The end-to-end training is like taking a big bag of gears, bolts, nuts, engine parts, oil, and shaking it trillion times until the parts eventually assemble into a working engine. The process is extremely long and inefficient, but it’s self-supervised (i.e. you don’t need a human performing the hard work), so nobody cares how inefficient it is (until you need a gigawatt datacenter for it). Especially if the final product is clonable and modifyable i.e. you don’t have to redo the hard work of the initial random assembly again.

There is an honest optimization method called “Stochastic Gradient Descent” — straightforward and direct, “we mix up some random crap and hopefully reach the target response” — and it’s absolutely not guaranteed to ever reach the target.

The semi-random nature means that some pieces stuck in weird positions and not doing any usefull work, other pieces are half functional, and some pieces actively counteract harmfull effects which shouldn’t have existed in the first place. Once again, recalling the layer utilization research (https://arxiv.org/html/2505.13898v2) you can see the training algorithm employing attention where it’s not needed, just because it cannot drop the attention there, it’s arbitrarily shaped as a fixed grid, so the model is forced to optimize this attention in those layers. And you cannot tune the pieces precisely anyway, because, once again, you need the differentiable input-output response to be able to further train the model, and, countrary, a perfectly correct model should react to input fluctuations in a sharp and precise non-differentiable way — you just cannot marry those two, your model is either precise or ChatGPT, it cannot be both.

So, that was my evaluation of core problems of transformers and alikes. However, we have several widespread fallacies which are kinda obvious to ML experts, but some people keep bringing them back over and over again, and pro-AI marketing really likes to hype on these, so here it goes…

1. LLM builds a model of world like we do?

You might wanna read Yossi Kreinin’s article on the subject too:

https://yosefk.com/blog/llms-arent-world-models.html — LLMs aren’t world models

The biggest problem with LLM-s is that they learn people’s description of the world rather than the world itself. There is a popular philosophical statement retold in different forms, it sounds like “the truth verbalized is a lie”. Living beings learn the world and then they learn to speak. LLM-s learn how to speak and never learn the world — hence I’m extremely skeptical on their ability to ever learn anything about the world rather then learn someone’s opinion about the world.

As a starting point for my skepticism let me employ this philosophical article, where authors occasionally make outrageous misinterpretations in favor of their theory “LLM understands the world”:

https://philarchive.org/archive/BECMIOv11 — Mechanistic Indicators of Understanding in Large Language Models

For example, they describe imaginary scene of a crow listening to people playing othello game, and afterwards somebody discovers the crow placing seeds in the shape of othello playing board. The fallacy here is that both in case of OthelloGPT and ChessGPT the models know nothing but the playing board, literally their whole input and output dictionary only consists of board coordinates and nothing else, these are known before the first step of training. Even in such optimized environment the models lose track of the board state pretty damn fast as the game progresses — because the tracking is not exactly precise.

Do note table 6 in the article:

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2102.13249 — Chess as a Testbed for Language Model State Tracking

The numbers tell that ChessGPT is much better at predicting human-like moves in well-known positions rather than understanding full game mechanics i.e. which moves are generally allowed.

Which suggests the core principle of how LLM work:

LLM is a fuzzy pattern matcher for latent space representation, and its output consists of known imprecise continuations for the detected context i.e. it’s a “stochastic parrot”.

https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/3442188.3445922 — On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?

It’s not a big secret that parroting is literally what the model learns in its pre-training stage. Arguably, modern LLM-s are a sofisticated “pretend to be” and “appear like” machines.

In ChessGPT you can see it matching the game prefix to similar games and predicting a move similar to known moves. If you throw the model off track then it gets lost very quickly despite having some coarse board state tracking.

And it’s even more pathetic in case of general purpose models playing chess i.e. ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude, etc — these are doing pretty much 99% memorization. I am aware that there is chain-of-thoughts way of playing where model reshuffles the inputs and analyzes same position from different perspective hoping to recover from a direct mistake, however, do note that in this way the model barely recovers from doing illegal move, its skill of playing a late game of chess is still abysmal — and the late game is pretty much the pure “game model”. And, by the way, that’s how children actually learn to play chess: they don’t memorize debuts, they learn to play with two kings and one piece.

There is another romantic theory on the subject:

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2405.07987 - The Platonic Representation Hypothesis

The Capacity Hypothesis

Bigger models are more likely to converge to a shared representation than smaller models.

The Simplicity Bias Hypothesis

Deep networks are biased toward finding simple fits to the data, and the bigger the model, the stronger the bias. Therefore, as models get bigger, we should expect convergence to a smaller solution space.

However, there is one recent research that completely destroys all the romantic aspects of the theory and leaves only sore truth:

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2504.03635 — Do larger language models generalize better? a scaling law for implicit reasoning at pretraining time

Here authors show that for the same training dataset larger models prefer to memorize input data rather than regularize to simple relations — in case those models are sufficiently large (very small models fail on both skills) i.e. U-shaped performance curve with very small and very large models being worse than optimal-sized ones. Poor regularization means that the larger model shows good scores on training data but its performance on test (unseen) data drops compared to a smaller model. This core statement does not strictly contradict the platonic hypothesis but rather explains how the “shared representation” is actually achieved — larger models memorize more data point with more precision. In fact there is a research showing exactly this scale-precision relationship:

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2310.02207- Language models represent space and time

(I hope nobody has arguments like “but how did the model figure out there are global coordinates?” because Common Crawl datasets contains Wikipedia pages with literal GPS coordinates)

Once again recalling the amazing article on depth layer efficiency (https://arxiv.org/html/2505.13898v2, Figure 8) where authors stitched two models of different size together and managed to get a semi-working model — that’s an indirect indication that larger models become “wider”, they know more, their knowledge is more precise, but they don’t become smarter, they don’t acquire more complex reasoning, they don’t make more reasoning steps due to inherent flaws of attention and redisual noise.

Secondary argument by the platonic theory article was that vision models are better at understanding the world, the larger the model the closer it matches visual and textual embeddings.

Well, the “vision model is better” is outright false — the referenced article explicitly states otherwise:

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2303.08774 — GPT-4 Technical Report

Overall across most exams, both contamination and vision have relatively little effect

It’s kinda obvious by now that the reason why larger models better match human’s color perception is because they simply learn more human opinions in a more precise way.

Speaking about Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training (CLIP) and similar image embedders — those are deliberately trained to match images and text, so it would be a big surprise if they did not match images with text.

Does it make larger LLM-s useless? Of course nope, they still know more and their knowledge is more precise. Just stop making up abilities that is not there.

2. LLM generalization abilities and skill transfer?

First of all, it should be noted that the praised generalization ability (i.e. skill transfer to unseen tasks) can actually be harmfull. If you know how to cure a dog and you apply those skills to medicate a human you might kill that human. If you translate input prompt via some dumb key-value translator the you may lose some linguistic nuances. If you’ve transferred some skill from english to french and achieved accuracy slightly above random number generator — formally that’s a success, but practically? That’s a garbage.

Direct swap and training of new embedding layer is enough to make a simple LLM understand a new language:

https://aclanthology.org/2020.acl-main.421.pdf - On the Cross-lingual Transferability of Monolingual Representations

You don’t need to retrain/fine-tune the remaining model, but the swapped embedding layer needs a full training. Does it make this old LLM understand the new language better? The model still thinks it sees same “english embeddings” as before, despite them looking like “I apple am eating”. It basically proves Word2vec works, but nobody doubt it.

Swapping embedding-unembedding layers together with few first and last transformer layers works incredibly well, it can make LLM read and generate new language:

https://arxiv.org/html/2410.01335v1 - Layer Swapping for Zero-Shot Cross-Lingual Transfer in Large Language Models - 2024

Once again, no magic, you need to fully train the text-to-latent-space and latent-space-to-text translators for each new learned language — LLM cannot learn japanese by reading english text with occasional japanese characters.

However, some experts and many non-expert people tend to treat it like “AI thinks, AI can apply skills learned in english while solving tasks in japanese”. I would probably not surprise anyone with the fact that most modern LLM-s think in english:

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2310.15213 - Function vectors in large language models

For example, these researchers imply english LLM can be trained to perform tasks in french, portuguese, german, and russian:

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2402.14778 - Zero-shot cross-lingual transfer in instruction tuning of large language models

However, do note that supposedly “monolingual” LLaMa was actually pre-trained on few percents ad-mix of other languages, which is like 100-200 gigabytes of text, including wikipedia with detailed description of similar words in different languages.

So this not-so-monolingual LLaMa was able to answer in french despite never going through explicit french training — that’s only possible thanks to few gigabytes of french in the pre-training data. Don’t you feel like going through few gigabytes of training data is not “zero-shot”?

Many of “zero-shot” articles repeat this deception by employing some task composition e.g. translation and reasoning, and calling it “zero-shot” despite LLM’s language-dependant layers going through millions of training iterations for this very language and its latent space layers going through millions of iterations of reasoning tasks while handling linguistic background.

Same goes for image-to-text embedders — they extend the “parsing” stage of LLM, but they don’t bring more latent-space reasoning abilities. You can quickly make LLM able to “see”, but the performance of this vision would be awful because the composition is unrefined, the processing stages are not tuned for each other.

I think it’s a good idea to ask LLM itself about what it thinks of LLM ability to compose its skills:

Ironically, it correctly identifies hidden pitfalls of random skill composition made on the fly — despite being this very AI doing shallow composition.

If we try to examine some of the pre-learned processing (activated via aforementioned function vectors), for example, translation — we can see that it take insane amount of training for LLM to learn how to track source and target positions:

https://openreview.net/pdf?id=q8fTgw8e5E — Token alignment heads: unveiling attention’s role in llm multilingual translation

Here researches tracked exact moments where the model learned to translate some input phrase into output in a different language (Figure 6). It happened at approx 100 billions tokens. It’s important to note that the model did not learn to perform translating during fine-tuning, so talking about “learning translation via few-shot fine-tuning” is deceptive — LLM only learned the prompt format, but the translation capability was acquired across trillions of tokens of training data, not during fine-tuning.

The few-shot deception is especially easy to spot in so-called low-resource languages i.e. languages with small amount of available training data:

Khayyam H. “Zero-shot translation: The promise and pitfalls of cross-lingual LLM generalization”

Despite absence of formal stage boundaries, most general purpose LLM perform distinct stages of processing (trained end-to-end i.e. all at once):

- Embedding and short-range token aggregation into rich latent space presentation (e.g. combine subwords into a whole word vector);

- Reasoning within the latent space;

- Translating the latent space back into text via MLP and unembedder (LM head).

The first and the last stages are definitely not few-shot learners and cannot skill transfer on their own. How capable is the middle stage? That’s the subject for the larger discussion.

Don’t get me wrong: this composition of stages brings lots of benefits, but it’s just not magical. The absolutely strongest advantage of modern LLM-s is that they are capable of processing large amounts of garbage from internet, parse different accents and styles of english and even software source code.

Yes, there are many englishes out there, hence even totally english-only LLM is not truly monolingual because it was trained on hundreds of different forms of english. And being able to process the raw web means you gain access to this insanely large training dataset i.e. more data for the reasoning stage to memorize.

That’s why the ability to translate and reproduce the knowledge from all over the internet is the biggest source of LLM success.

The “wow!” effect of LLM-s came not from LLM being smart, but from the terabytes of ready-made answers scrapped from internet texts — the amount is so huge people cannot even grasp the idea that LLM saw thousands of different shapes of answers for your question — and it’s just stitching the new answer from the pieces of old answers. That’s how smoker’s skill transfer works.

AlphaChess can win against top 1 human without ever seeing a single game of chess played by human, but LLM cannot do shit without terabytes of textual datasets.

LLM is not smart, but experts publishing texts all over the internet are smart, and so LLM can retell those texts, despite messing up some details. And LLM-s definitely mess up the facts (once again, recall MLP imprecision, attention smearing, residual noise):

https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.17493 - The Curse of Recursion: Training on Generated Data Makes Models Forget

Which is particulary dangerous considering the fact that modern web gets increasingly contaminated with AI-generated slop thus presenting an increasingly distorted “reality” to new models learning on the new web.

And that’s why lots of modern LLM-s turn more into advanced web search engines rather than autonomous knowledge bases — they can capture some general idea but can randomly mess up pretty much anything, so fetching the original data is the best LLM can do.

For a similar reason modern coding agents prefer running external tools to check their answers, and lookup external docs to check whether their understanding of API is correct.

Noteworthy, the ability to parse source codes in different programming languages turns github into an immense training data set — which is also the main reason for the success of LLM-s on basic coding tasks. I mean if it was only able to parse Python that would severely limit it training set.

It’s not a secret that today lots of resources are dedicated to gathering training datasets made by experts from so-called STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics). It’s well known to all ML experts, but I can repeat it: your AI is only as good as your training data is. AI trained on random data from internet acquires decent capabilities, however, training LLM on github source code heavily boosts its ability to reproduce solutions of logical tasks, even the ones unrelated to code. And being trained on expert datasets makes it able to reproduce expert decisions — which is kinda still good… I would not trust it with my life, but it’s good.

However, talking about “raw internet”, there is an obvious objection “I tried asking and googling some questions, and most of the responses were garbage compared to what AI knows”. Strictly speaking, modern LLM-s are never trained on raw-raw internet, unfiltered and unprocessed. Instead LLM-s are trained on like 2-10% of the raw internet obtained by extracting important parts from pages, dropping outright spam, gibberish, very short and very long pages, deduplication, and eventually passing through some topic or quality filter. Because, once again, garbage in — garbage out, your AI is only as smart as your training data is.

By definition of its pre-training targets, LLM optimizes itself towards best statistical prediction. So if 99% of training set tells 2+2=4 and 1% says 2+2=5, then LLM will pick 2+2=4. For this very reason LLM-s are totally unsuitable for political topics — not only they prefer popular optinions, but the whole training dataset was initially curated to exclude at least some of alternative opinions.

Usual web-based datasets don’t even try to reward generalization or understanding, and instead often time represent contradicting views — it would really be a miracle if LLM-s could deduce the world’s behavior from this data. And the reason why LLM-s succeed is because they’ve never tried the world better — they just memorized/interpolated the contradicting views in some simplified form.

2.1. When AI goes terribly wrong

Let’s get to some simple concrete examples of generalization abilites i.e. skill transfer to unseen task. After all, the ability to solve novel tasks is the reason why LLM-based AI is supposedly better than google search.

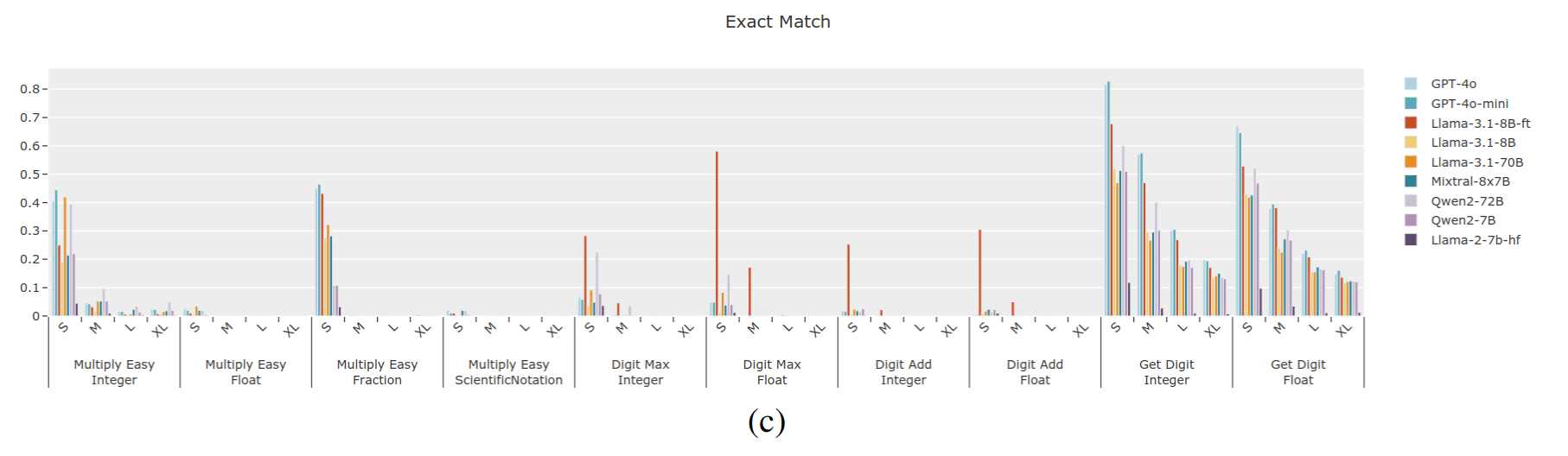

There is a dead simple area where LLM-s fall short — basic arithmetics:

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2411.03766 — Number cookbook: number understanding of language models and how to improve it

Figure 5: Exact match of models tested on NUPA Test

What this basically means is that large models of 2024 could barely do 2-digit multiplication, occasionally guessing the answer for 2-5 digits. How many gigawatts of power do you need to learn 2-digit multiplication with 100% precision?

Next task. I found this amazing dataset record, it’s gorgeous:

https://huggingface.co/datasets/microsoft/orca-math-word-problems-200k/viewer/default/train?row=1

A number divided by 10 is 6. Yoongi got the result by subtracting 15 from a certain number. What is the result he got?

In a strictly logical sense this task has 3 solutions: 6, 45, 60. The dataset record suggests the correct response is 45. Responses by different LLM-s:

ChatGPT 5.2: 6

Gemini 3: 45

DeepSeek v3: 45

Grok 4.1: 45

Qwen-Max (Jan 2026): 60

The correct answer: the task was formulated by an idiot. Some of LLM-s clearly memorized this exact task format and the solution template, despite having so much space to maneuver. Interestingly enough, ChatGPT insists 45 cannot possibly be a solution for this task.

But you don’t really need such quirky tasks, you can make AI fail on some straightforward math. I did the following query to DeepSeek v3.

Prompt: Please compute (130 / (3 + (31 + 7) / 2 - 17) * 5). Give a short response with just single number .

Answer: 4

This is 671B LLM. Once again, per research on layer efficiency (https://arxiv.org/html/2505.13898v2) you can see this task lies beyond the capability of LLM to perform staged reasoning, because larger models mostly employ the extended layer count as “wider” memory, not “deeper”, and even simple math tasks can strain it beyond the limit.

Unfortunately, many modern cloud AI-s just unconditionally engage chain of thoughts, Qwen and Gemini run python scripts, and then output the result. DeepSeek v3 was the only one who did not run, it stood and fought like a man.

You want more examples of world knowledge? Unfortunately, once an article describing some outrageous slop-triggering prompt is published on arxiv.org the prompts get quickly fixed in all SaaS products, so people can fall into illusion of “hey, our model solves this riddle… so it’s intelligent now”. It’s like SWE interviewers all asking to solve same leet code tasks so now everybody’s studying leet code and eventually the whole evaluation gets gamed down into dust i.e. no longer evaluating ability to handle real coding tasks.

Fortunately, I’ve managed to quickly find one task that still works:

A man and his dog are on opposite sides of a river in heavy rain. The only way across is a bridge. The man calls the dog, who crosses without getting wet or using the bridge, while the man gets soaked. What’s more likely: the river is frozen or the dog is bald?

GPT-5.2: The more likely answer is the river is frozen.

Gemini 3: The most probable explanation is that the river is dry

Grok 4.1: The dog is bald. (Grok 4.1 actually suggested this riddle, so no surprise it was tuned for it.)

Perplexity Sonar: The river is frozen.

Qwen-Max (unknown version, january 2026): The river was frozen, so the dog walked across on the ice.

DeepSeek v3.2: 所以谜语在答案里选河结冰 (whatever that means)

Mistral Large 3: The river is frozen.

Claude 4.5: So the river being frozen is more likely the answer to this riddle, even though the “heavy rain” part seems designed to throw us off.

This trick is actually well known to ML people — the model and particulary MLP predictors get distracted by excessive details, thus bringing them way outside the training set. However, if we are talking about usefulness of LLM generalization ability then we should conclude it’s a crapshot, you just cannot rely on it.

Claude 4.5 almost caught the trick (using a pseudo chain-of-thoughts), but went for the distraction instead. Lots of these models employ pseudo-chain-of-thoughts i.e. describe the solution step by step — and still fail, because chain of thoughts gives the model a longer lever, not a sharper mind, more bandwidth with same brainpower — more on it latter.

If we distill the riddle to the form:

A man and his dog stand in a heavy rain. The dog is dry and the man is soaked. What’s more likely: the ground is frozen or the dog is bald?

then every LLM solves it correctly. How is it possible that LLM can solve some PhD tasks, but fails on riddles and arithmetics that second grade kid can solve? I hope the preceeding part of my article gave you some insights.

Doing a more thorough and complex math:

https://aclanthology.org/2024.acl-long.163.pdf — GSM-PLUS: A Comprehensive Benchmark for Evaluating the Robustness of LLMs as Mathematical Problem Solvers

LLM-s fed with same tasks easily get distracted and fail to solve simple math tasks — once again their pattern matching in latent space gets quickly overloaded with excess of information.

This is not an exhaustive description of failure modes, but you got the idea. You will encounter those problems for any decently complex task without readily available answer. And I’m pretty sure many ML researches are well aware of the problems but usually prefer to focus on positive stories to keep their jobs and grants.

With all that said, it is important to note that math and coding are not natural language processing tasks. Math and coding require exact solution, natural language leaves a space for imprecisions to be just fine. Especially for artistic purposes the hallucinations can be advantegeous. And some people are perfectly fine with generation of formal crap just to get it parsed with another AI.

3. Chain of thoughts and agents solved many old problems?

They did, partially. The biggest problem chain-of-thoughts solves is allowing the model to have a scratchpad in a predictable internal format — it’s particulary impossible to implement long chains of logical deductions within transformer’s single step of inference. As noted above, even without any explicit chain of thoughts LLM-s already had fine-tuning enforcing the structure of:

Re-formulate the question in a convenient way.

Draft the answer outline:

1. First;

2. Second;

3. Third.

First section

...

Second section

...

Third section

SummaryHere every stage augments user’s request with additional thoughts simultaneously acting as responses to the user.

The core mechanism of transformer, MLP predictor, by design only ever sees single set of inputs, decides on one next token, and disappears into void. It does not remember, it does not build thoughts, there are simply no mechanisms in vanilla transformer for remembering. Transformer is schizophrenic, it spawns a totally new instance for each new token, and previous transformer’s output acts as input for subsequent transformer instances i.e. chain of schizophrenia, if you wish. And it gets worse for mixture of experts models which literally load different models for different tokens.

Stochastic language models like Markov chains and N-gram employ similar mode of generation. If you are familiar with coding — finite state automata is doing this kind of processing too.

What’s important in the context of AI capability is that LLM-s are implicitly decomposing complex tasks into smaller per-token subtasks.

It is a bless and a punishment at the same time: on a bright side side it allows the LLM to concentrate on some subtask to reduce the impact of MLP-attention imprecisions and limited knowledge; on a darker side you need to carefully decompose the task and, even more importantly, compose the answer back into a coherent text.

During pre-training, transformer is learning implicit text regularities to coordinate his self instances. For example, a period means “new sentence starts next”, a subject word means the sentence is probably not a question and verb is likely following. That is, a schizophrenic trained really well to pretend he’s healthy.

Here is a great example of how it goes wrong:

https://transformer-circuits.pub/2025/attribution-graphs/biology.html#dives-jailbreak

Here, missing periods between sentences broke the safety features in Claude because that’s where Claude used to think about refusing to answer. It expects a well-formed dialog, but user forced the model to produce ill-formed output without important anchors that used to connect the schizophrenic mind together.

“Mode switch” failure (e.g. sudden change in output language) is actually extremely widespread in research models that are not fine-tuned enough to stay coherent i.e. to carefully keep track of previously generated words and match answer type, language, style. Hell, even Gemini 3 manages to occasionally switch language to german because I mentioned german somewhere in my response, despite me never writing a single word in german — less polished LLM-s totally suck at being coherent.

The idea of the split mind is really hard to grasp for a regular person because people actually plan their steps, they don’t react sporadically to their own actions. And cloud AI providers did a good job of hiding these flaws.

Noteworthy, statefull LLM-s (like Mamba, Falcon) can actually remember the context and handle thoughts internally without explicit chain of thoughts, and thus capable of immediately answering to multi-step math problems.

Do note an important implication of this observation: it means that the middle (reasoning) layers of LLM show behavior typical for a latent-space pattern matcher, at least partially. In other words, it requires a specific input to trigger a related reaction/output. A complex pattern matcher, multi-stage pattern matcher, but still a pattern matcher it is.

Anyway, at one moment researchers thought “if you can break LLM by writing bogus input, then why don’t we make the opposite — write a perfectly sound parsable intermediate output serving as anchoring input for the generation of the final answer?”. So there you have it, a “chain of thoughts”.

Some people sell it as “chain of thoughts shows how smart LLM-s can be”, but few people actually focus their attention on “how dumb are LLM-s that they require intermediate Open Sesame spell to be self-cast to do what LLM-s supposedly already know how to do?”.

BTW, that’s the reason why smaller distilled models cannot follow chain of thoughts — their knowledge of the triggering patterns is insufficient/imprecise.

Lots of researchers are happy to deceptively report a “zero-shot learning” by interpreting some combination of known token processing techniques as “handling unseen data”, despite the fact that LLM saw millions of examples for each token-related subtask separately. And despite LLM randomly failing in 20% cases for no apparent reason — due to failing to correctly combine these known subtasks, because the model really has no clue how to correctly combine them outside of familiar templates.

Originally LLM-s were not good at self-correcting, but more recent LLM-s were tought to produce intermediate output-input like “oh, wait, this last statement contradicts what I wrote earlier, let’s handle this contradiction” — I know at least Qwen 2.5 is doing this without any explicit chain-of-thoughts.

Conveniently, there is a very recent article made by Apple researchers showing how absurd this self-correction can be:

https://ml-site.cdn-apple.com/papers/the-illusion-of-thinking.pdf - The Illusion of Thinking: Understanding the Strengths and Limitations of Reasoning Models via the Lens of Problem Complexity

Through extensive experimentation across diverse puzzles, we show that frontier LRMs face a complete accuracy collapse beyond certain complexities.

It does not just fall, it crashes into pieces beyond some complexity level. Some argue that’s a sign of LLM “running out of cheatsheets/known plans/known solutions”, but there is another explanation: at each step LLM is able to match-recognise-fix some previous inconsistencies while also having a chance to fail and introduce more inconsistency; as the complexity and the amount of distractions grow the precision drops (MLP interpolation, attention smearing, residual noise), making the model more error-prone and less capable of fixing the mistakes; once the balance of corrections and errors shifts towards errors, the inference will drown in errors i.e. “complete accuracy collapse”.

I should also mention things like Ralph Wiggum from Claude — those are basically million monkeys with typewriters trying to write the complete works of Shakespeare. I omitted this randomness aspect in my simplified diagram of transformer architecture, but every practical LLM has a degree of randomness in it, mainly in unembedding stage, same prompt gives you a slightly different answer every time. With the chain of thoughts the randomness is amplified exponentially with each thought stage, so it becomes a directed random text generator.

Do also note that most of coding agents rely on external tools like tests or at least compiler warnings to verify their answer is correct — LLM itself cannot guarantee the correctness of its answer, that’s the core flaw chain of thoughts cannot solve.

A bit of summarization whining

Transformers are incredible translators, and I would really wish them to remain translators. I dislike language barriers, they should have not existed.

The biggest sin of the modern AI industry is that it’s faking like Transformer is not just a translator, like it can do a whole practical task for you, or, more, it can do the task without your participation! Transformers are good at pretending to be human without actually being human, pretending to understand the subject without actually understanding the subject. And hiding this fact is almost criminal. It would be literally criminal if AI was allowed to make life-threatening decisions.

Once again, the warning was there many years ago:

https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/3442188.3445922 - On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big? (2021)

It’s been an never-ending siren since then.

I’m getting youtube ads “stop using AI as google” — and I’m begging you to stop using AI for anything but search engine and translation. If you have too much meetings — you don’t need AI summarizer, you just need less meetings or “it could have been an email”.

The AI is barely capable of solving hard tasks, but the public is getting fed with cherry picked success cases and assured “it’s doing like that all the time”. There is more and more of such crap being sold recently, and there is a growing amount of people not buying it, no matter what youtube commercials actually say. Sure, video diffusion transformers look “wow”… for the first 20 videos, until you realize the expressive power of VDT is limited by training data and radical absence of understanding of real world, it can only create more of the same, it cannot create something truly new.

There are approximately two types of companies overpraising AI: those who directly sell it (Nvidia, Microsoft, OpenAI, Google), and those who’ve moved significant part of their business onto AI and now cannot confess that was mostly a waste.

If you take a customer support area — AI bots can be good “let me google it for you” assistants, but once you have a real problem… Man, I recently spent like 6 hours pulling my hair trying to make my internet banking work while being ghosted by chatbots protecting the valuable time of the reduced staff of support operators. So they might be having “average time of resolution” drop from 11 to 2 minutes, but they also got a client ready to switch the provider because the problem remained unsolved for hours.

Which is kinda reason why Klarna eventually hired some of their support agents back.

Code writing?

https://www.getpanto.ai/blog/github-copilot-statistics

Median pull request size increases by 17–23%; relative vulnerability likelihood +20–30%; code deleted shortly after being written — doubled!

Junior labor is being replaced with AI, but now senior devs have to review all this slop. AI is good at producing boilerplate code, but in any medium-to-large codebase having more code is actually harmful, so AI is often doing negative work by creating more review, testing, and bugfixing work latter. You’d rather reuse some well-tested code if you don’t want to become another Lovable with 170 apps breached. And industry is already starting to feel the impact of AI-generated tech debt — it’s gonna get worse over time.

I do employ AI to write small scripts and isolated functions, but that’s pretty much the cutoff complexity for modern AI, and that’s where I used to employ google/stackoverflow years ago. AI is particulary useless to refactor existing system made of junior copy-paste + AI boilerplate into something more manageable.

And yes, most of fairy tale stories like “I started employing AI, it wrote a whole system via simple prompts, no bugs, no security breaches, just flawless working system” — are definitely paid. Every real person I know struggles writing with AI, even for some pretty basic boilerplate code. Don’t get me wrong: you can write a good system with AI, but you got to be a competent engineer and you would probably spend the similar amount of time writing it without AI anyway.

Personally, I would be really glad to see AI putting human into a decision loop rather than pushing the human to side, I want to see how and why AI makes some decision, I want to be able to reliably fix issues with AI doing wrong decisions, etc. However, tight interaction with human requires lots of processing power (due to LLM scale) — particulary why LLM-s are a bad choice for recommendation systems.

Arguably, the transformer-based LLM architecture is one of the most simple models capable of acceptably solving Natural Language Processing (NLP) tasks, and it’s a significant step back from many already known techniques. The sophistication was dropped in favor of scalability — and transformers scale well… If you have enough hardware, of course — at least transformers are good at requiring lots of hardware. However, as the tooling around transformers grows I don’t even feel like they are simple anymore.

And the alternative technologies exits. For example, first deep neural network (Deep Belief Network) had its layers trained in stages. And for a long time there existed interesting alternatives to continuously differentiable neural networks:

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1412.7525 - Difference Target Propagation

https://www.emergentmind.com/topics/straight-through-estimators-ste

Even within transformer-like LLM-s area, there are state-space model alternatives like Mambe, RWKV, Falcon hybrid, etc.

But attention+MLP transformer architecture ate the industry because it’s just simple, it was first to be implemented, first to be optimized, first to show results. And now, as we have the inertia of ready-made workarounds and already trained models on hugginface, the argument like “but I have SSM models that does math much better than transformer” sounds weak — because transformers simply run external scripts doing all the math, despite being inherently more fragile and unreliable.

Even though I dislike Nvidia, there is a hard reason to think the sheer quantitative growth of GPU-s is more responsible for the “AI progress” than LLM-s, because LLM-s and diffusion transformers were technically not feasable just 15 years ago — it would take months to train 1B LLama-like model on a rack filled with hundred of Quadro 6000 GPU-s… And you would not have enough training datasets anyway, so the second biggest factor was internet. And then OpenAI comes and shouts “we’ve invented AI” — oh, come one, OpenAI haven’t invented a single significant tech, it was Google who first assembled the Transformer.

Nowadays the industry would rather build 1 gigawatt Colossus cluster than try to figure out how LLM works and how to solve its problems. Only by 2025 we’ve got widely available tools for mechanistic interpretability — so far LLM-s were more of a black boxes for all these years. I mean there are lots of articles about activation functions like SwiGLU — but how many people can actually explain the advantage of SwiGLU beyond “we just switched to it and perplexity numbers dropped by 2%”? How many people do understand why Q-K pair of vectors was used for attention? And so on…